3 min Read

Fred Gmitter believes humans are hardwired to love citrus fruit.

“If I show you a picture of a lemon, your mind immediately smells the lemon,” said the University of Florida professor of horticultural sciences.

The millions of Americans who start their day with a glass of orange juice seem to prove Gmitter right.

Gmitter has spent much of his career breeding new varieties of citrus that look, taste and smell even better than the citrus you already know and love. Just a few of the things that make citrus special, according to him: The fruits range in size from that of a pea to that of a pumpkin. The trees are evergreen. Many types of citrus, such as oranges and grapefruits, are hybrids rather than distinct species.

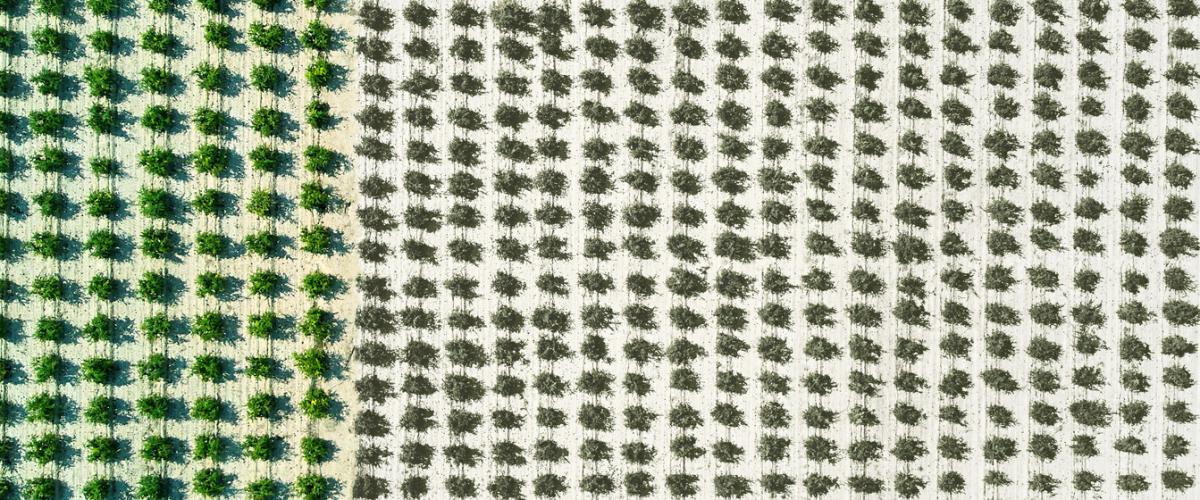

But a black cloud hangs over Gmitter’s work, and citrus production in the U.S. — and perhaps the world. A deadly disease called citrus greening disease, or Huanglongbing, has devastated the citrus industry in Florida, wiping out production in many areas and knocking down the state’s volume of citrus fruit by more than 75 percent in a dozen years. The crisis has affected the intricate web of people who rely on citrus for their livelihood, from growers and pickers to drivers and juice manufacturers to fertilizer producers. And though the disease has not hit California commercial groves yet, concerns are high that it soon might.

[imagetext stat="75%" description="of Florida's citrus industry has been devastated by citrus greening disease."]

[/imagetext]

To fight the disease, breeders like Gmitter are combining traditional research on plant attributes, like developing new types of root stocks on which trees are grafted, with a search for genes that could be edited to boost citrus trees’ ability to resist greening.

“We’re providing options to growers that will get them through until we might have a plant someday that is completely resistant,” he said.

Ugly Fruit

Citrus greening disease, in a sense, chokes the life out of citrus plants. Bacteria spread by an insect that feeds on citrus plugs up the tissue that moves nutrients, sugar and water through trees’ systems. The result is not pretty: leaves that are blotchy and mottled in color, rather than a lovely uniform green; weak spring growth with very small leaves that stand erect and look like rabbit ears; and abnormally small, misshapen and green fruits that taste and smell unpleasant.

While trees hit hard by citrus greening don’t die right away, “you look at them and wish they were dead,” Gmitter said. “They’re useless things.”

For Gmitter, finding a solution to citrus greening is about more than saving the citrus industry today — it’s also about creating a better environment for innovation.

“We would like to release new varieties with different tastes and scents,” he said, “but with HLB, it’s hard to convince growers to try them. You plant them, and the disease chews them up.”

That’s why at UF’s Citrus Research and Education Center, where Gmitter works alongside microbiologists, entomologists, soil scientists, economists, and others, “Everybody is looking for a cure or solution or way to work with this disease,” he said.

Complex Project

Gmitter — whose research group released the first publicly available citrus genome sequences in 2011 — aims to use gene editing to find surgically precise ways to change genetic characteristics of citrus trees. The goal is to make them more resistant, if not immune, to citrus greening, the bacteria that causes it and the insect that spreads it.

[quotation align="right" source="Fred Gmitter" attribution="Professor, University of Florida"]

We’re providing options to growers that will get them through until we might have a plant someday that is completely resistant.

[/quotation]

With a long laundry list of possible genes to target, the task is complex.

Once researchers have identified the correct genes — and there may be many — edited them, and tested them in a greenhouse, they’ll work with growers to conduct trials in the field.

Collaborating with growers will be key, Gmitter said, because there’s unlikely to be one silver bullet that will end citrus greening. Already, some growers have been able to make afflicted trees more productive by changing how they irrigate and fertilize their orchards.

“It’s not going to be what’s that one gene to knock out HLB and make trees immune forever,” Gmitter said. “Maybe we modify some genes and put that together with how you irrigate or control pests or fertilize to make trees more resistant. I view it as a mosaic of things that are going to come together.”